URSSI Conceptualization Survey Results

May 20, 2019

URSSI Community Survey - Initial Results

To better understand research software user and developer communities, we conducted a survey of research software users and developers. The focus of the survey was to gather information to help identify how to increase the sustainability of research software. To gather a broad range of perspectives, we distributed the survey to 25,000 NSF and 25,000 NIH PIs whose projects involve research software, as well as mailing lists of interested people such as the WSSSPE email list. In addition, we used snowballing by asking people to forward the survey to others who might be interested. This effort is part of the URSSI conceptualization project, which seeks to understand the diverse challenges and barriers that the research software community faces.

The survey had seven sections: Development Practices, Tools, Training, funding, Career Paths, Credit, and Diversity. Survey respondents answered a few questions about each topic, then, optionally chose one or more topics about which they answered more detailed questions. In this blog post, we discuss a subset of the answers to provide an initial look at some of the interesting findings. The full list of survey questions is available here. We are in the process of producing a complete analysis of the results.

Demographics

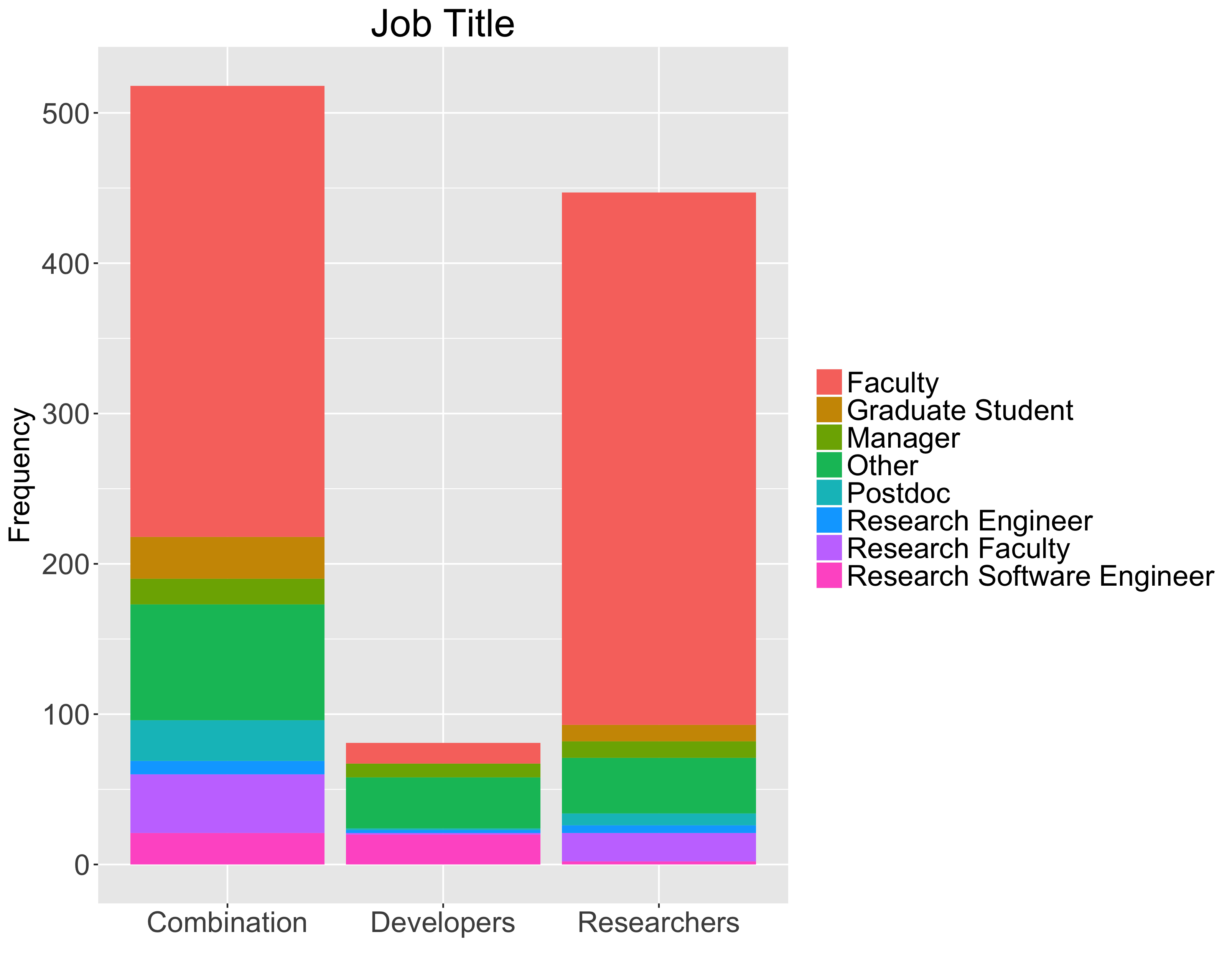

We received 1194 complete or partial responses to the survey. In order to help us understand the population, we asked each respondent to characterize their relationship with research software as either a Researcher (pure user), a Developer (pure software developer), or a Combination (both user and developer). Most respondents were either Researchers or Combination, with slightly more Combination. The figures below show two key characteristics of the respondents. A large majority are employed by educational institutions and are in faculty positions.

Development Practices

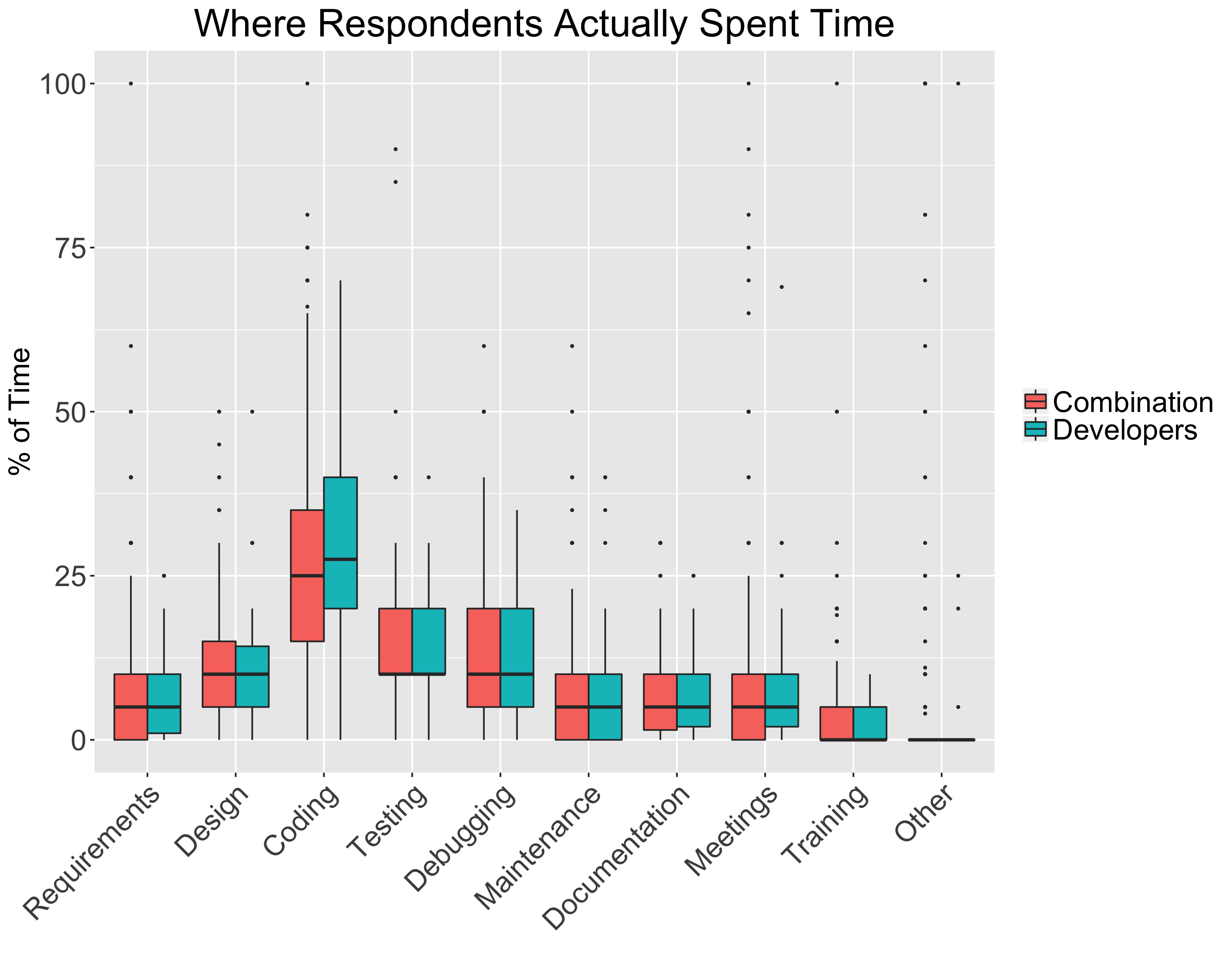

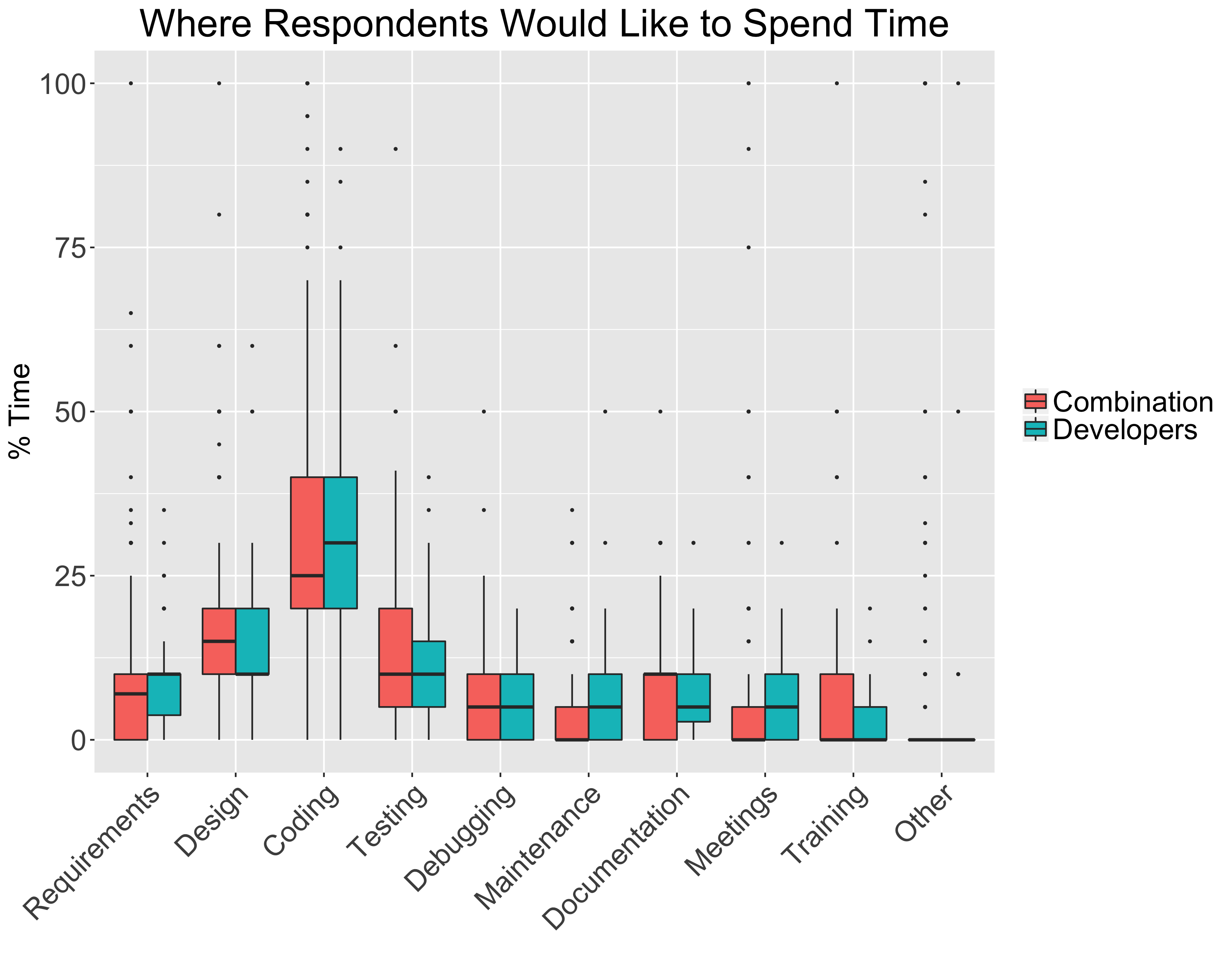

We first examine which aspects of the software development process consume the respondents’ time. We find that there is a discrepancy between where people currently spend their time and where they would like to spend their time (see two figures below). Respondents would like to spend more time coding, more time in design and less time testing and debugging.

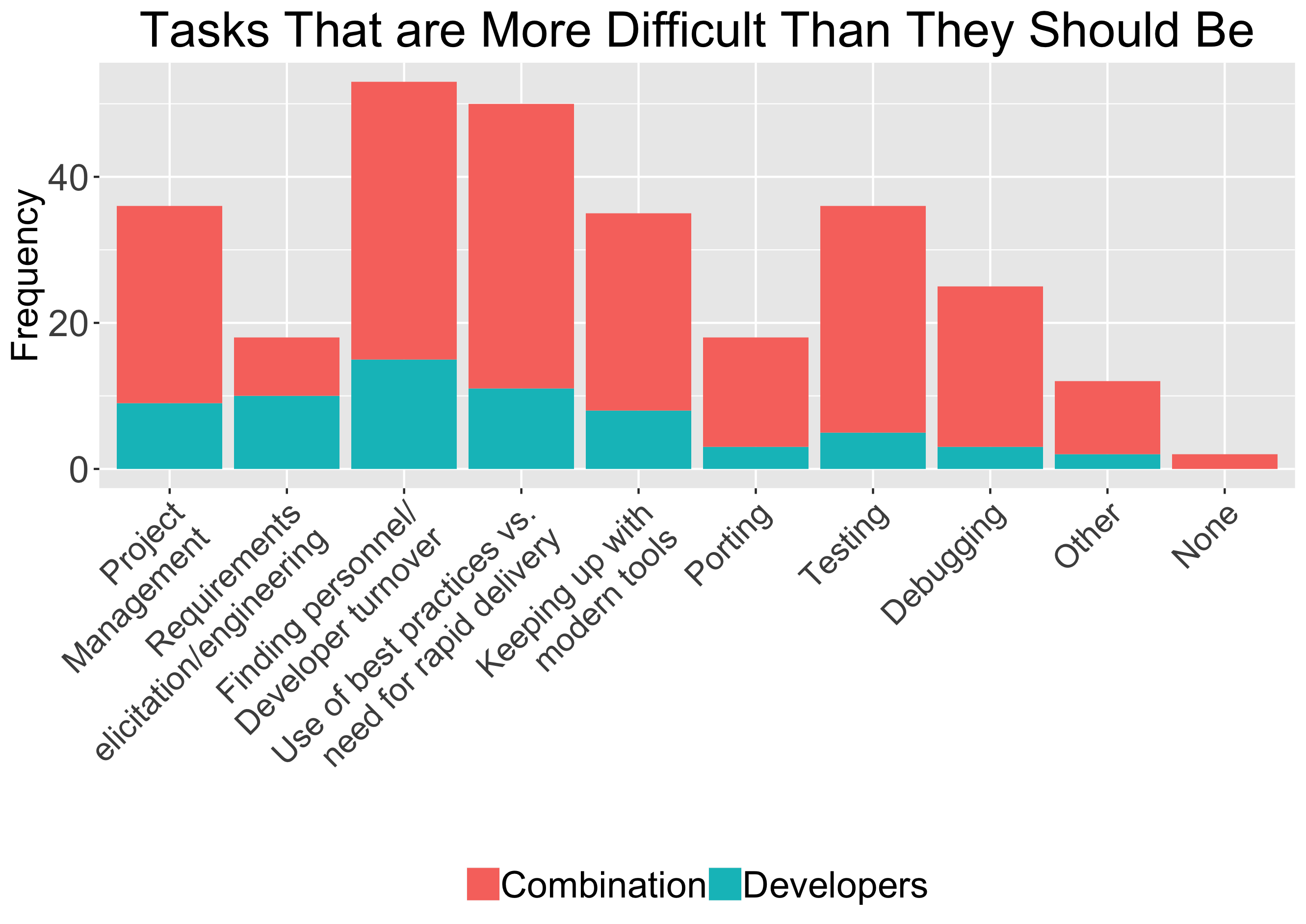

We next look at which aspects of the research software process are more difficult than they should be. As the figure below shows, the top two items deal with personnel turnover and balancing the use of best practices with the need for rapid delivery of results.

When we asked about the respondents’ use of various common software engineering practices, we found mixed results. The practices of commenting code and using descriptive variable/method names are used very frequently. The practices of requirements gathering, design, continuous integration, and coding standards are used less frequently. The practices of pair programming and peer code review are not used very frequently at all.

Tools

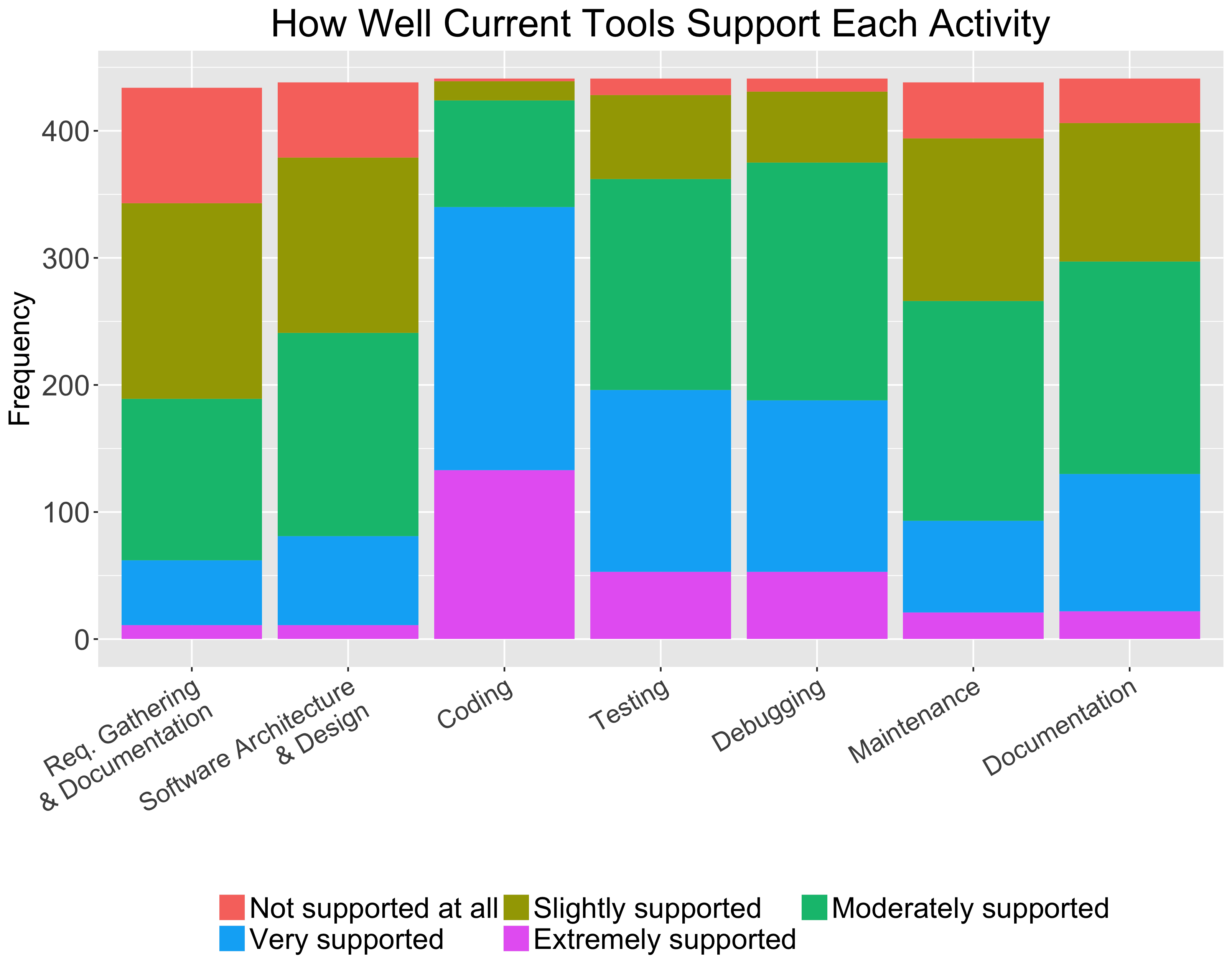

We asked respondents whether there was adequate tool support for various activities in the research software development process. As the figure below shows, the only activity where there appears to be adequate tool support is for coding. Testing and debugging have some amount of tool support. Overall, there is room for the development of additional tools to support the research software development process.

Training

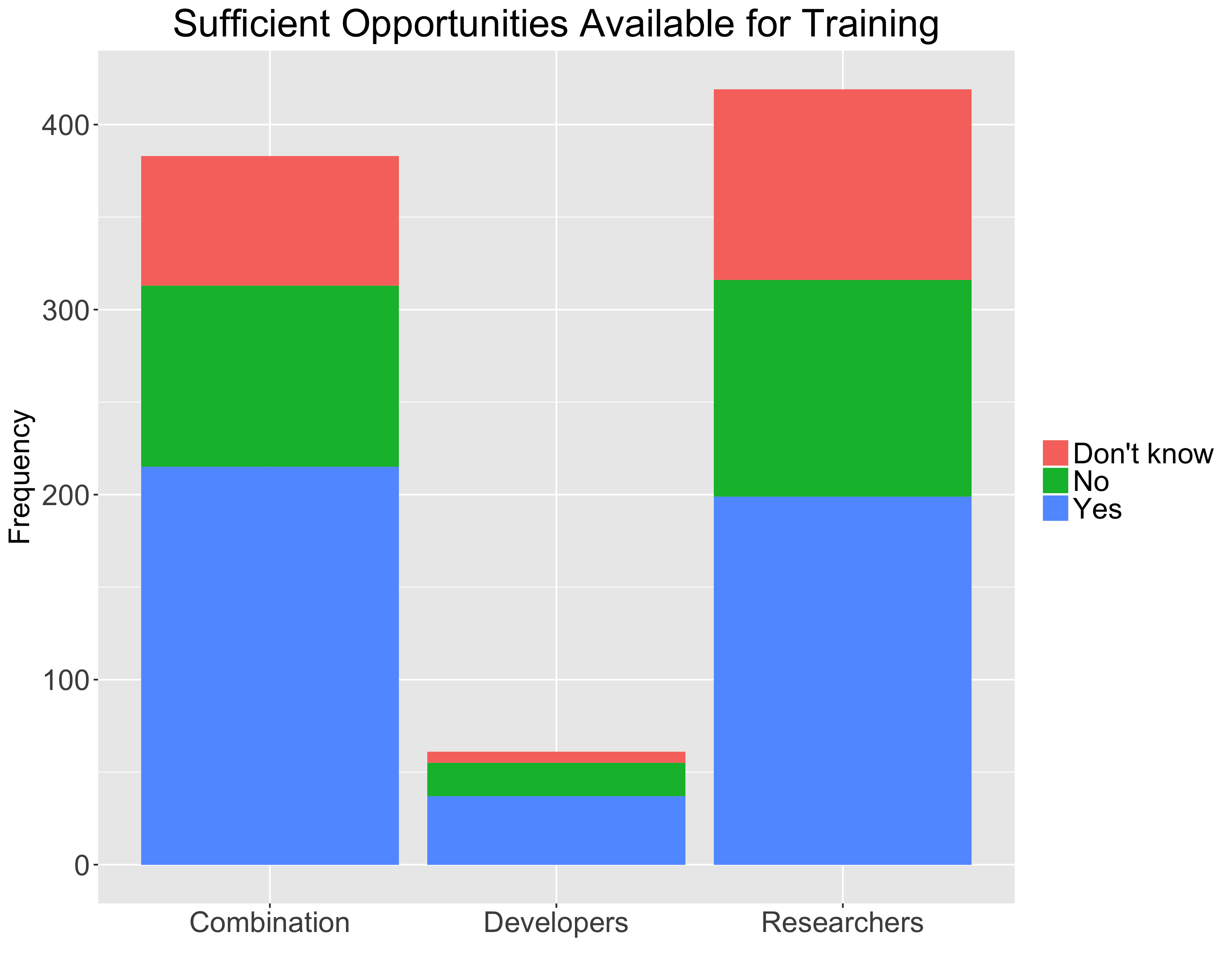

The story the results tell regarding training is interesting. First, the majority of respondents indicated they had not received software development training. Not surprisingly, this result was more pronounced for the researchers. For the combination and developers, closer to half have received training. Second, as the figure below shows, only about half of the respondents indicated there were sufficient opportunities for training.

But, more problematic, as the figure below shows, only about 25% of the respondents indicated they have sufficient time for training.

So, there is clearly a need both for more opportunities for training as well as for more time to take advantage of the opportunities offered. We believe that institutions should provide support (time and, when required, funding) for both their researchers and developers to attend training as part of their jobs.

Funding

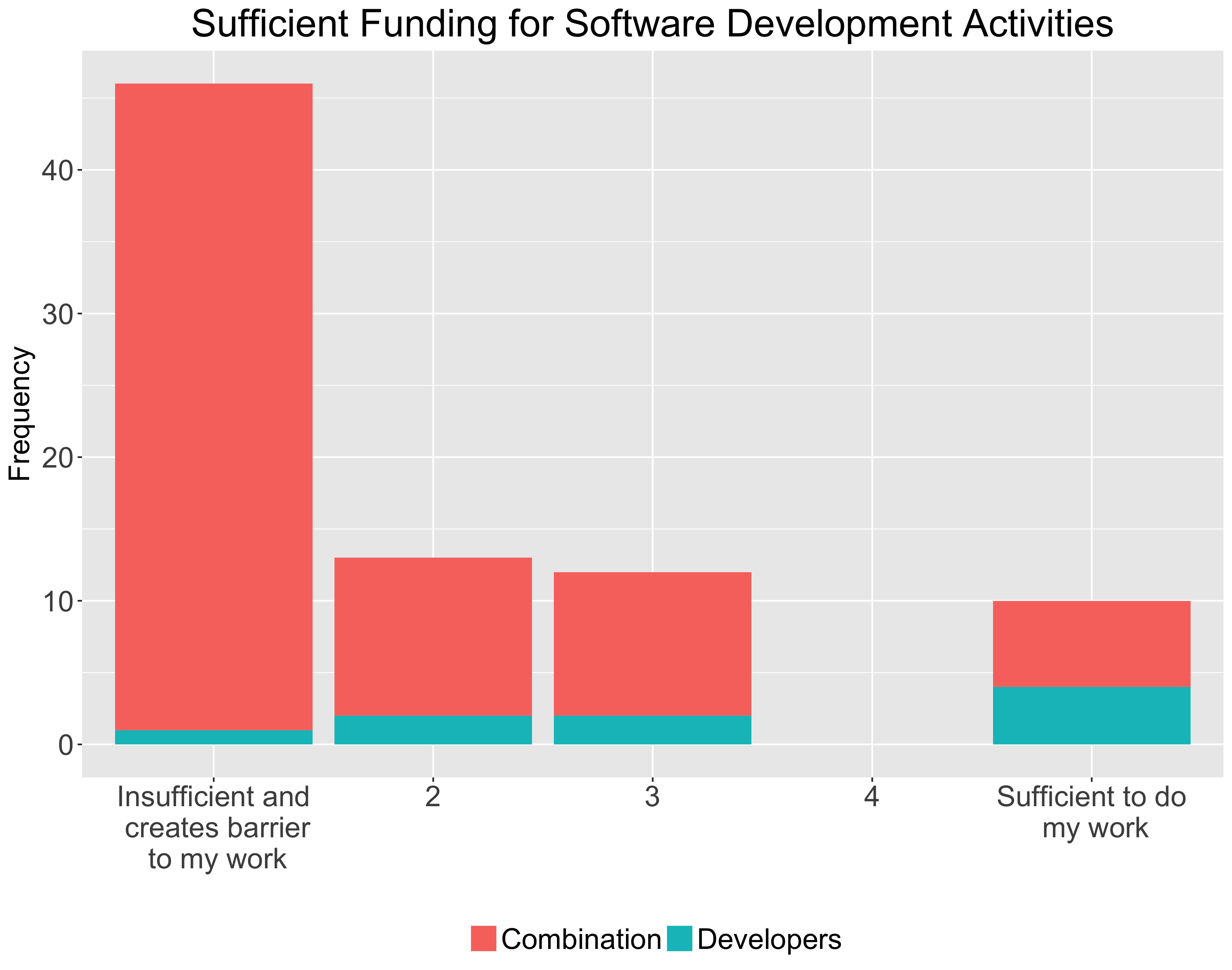

The availability of funding for various research software activities provides an indication of why some activities may be less frequent. A large number of respondents included funding for developing software in their proposals. But only about half as many indicated that they included costs for maintaining and sustaining software in their proposals. Overall, as the figure below shows, overwhelmingly respondents saw the lack of sufficient funding as a barrier to their work.

Career Paths

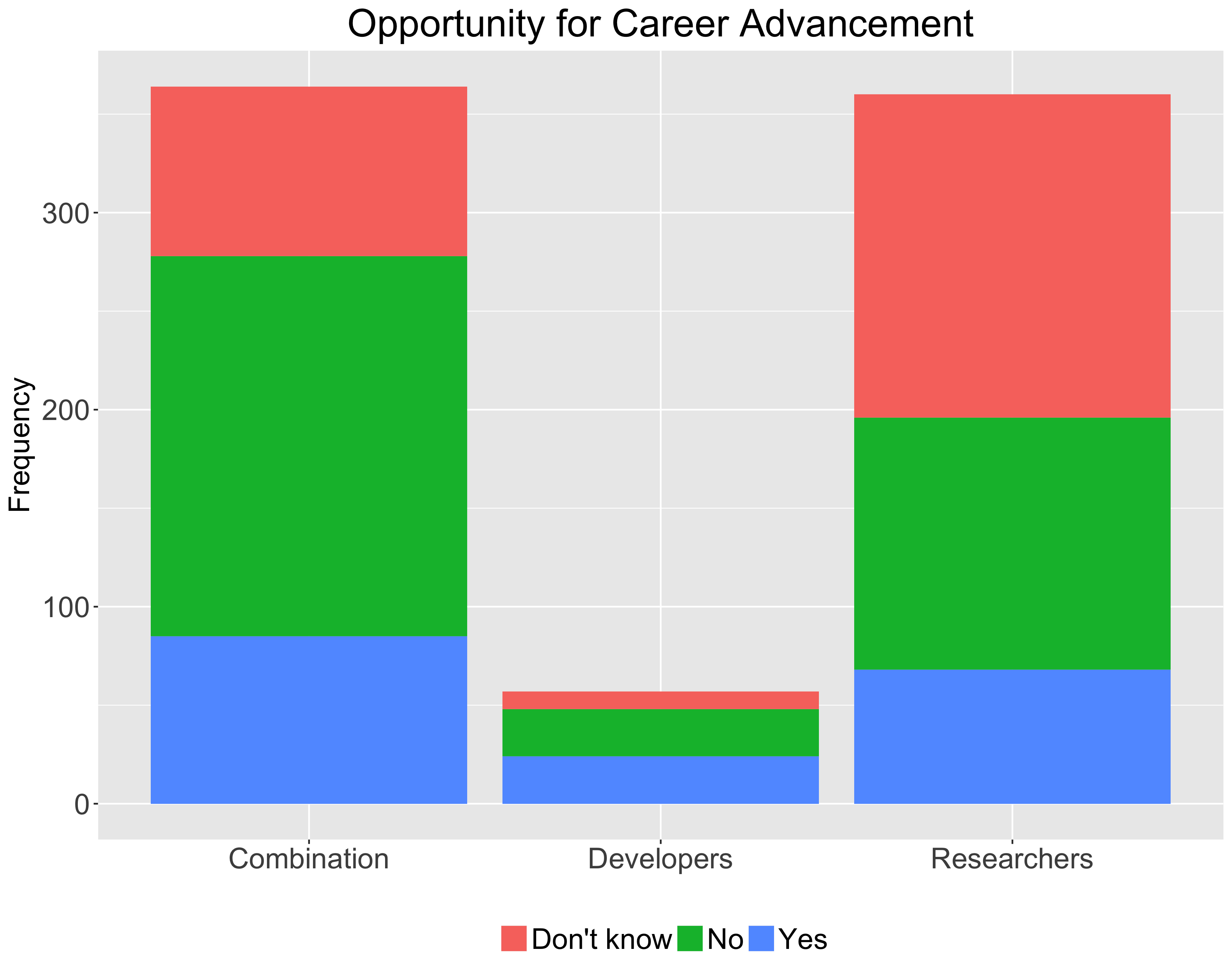

There still a need for better career paths for those involved in development of research software. The respondents’ titles vary greatly and include: postdoc, research software engineer, research programmer, software developer, programmer, faculty, and research faculty. While postdoc was the most common answer, the others were all given with about the same frequency. More concerning, as the figure below shows, the vast majority of respondents indicated they have no opportunity for advancement or they are not aware of such an opportunity.

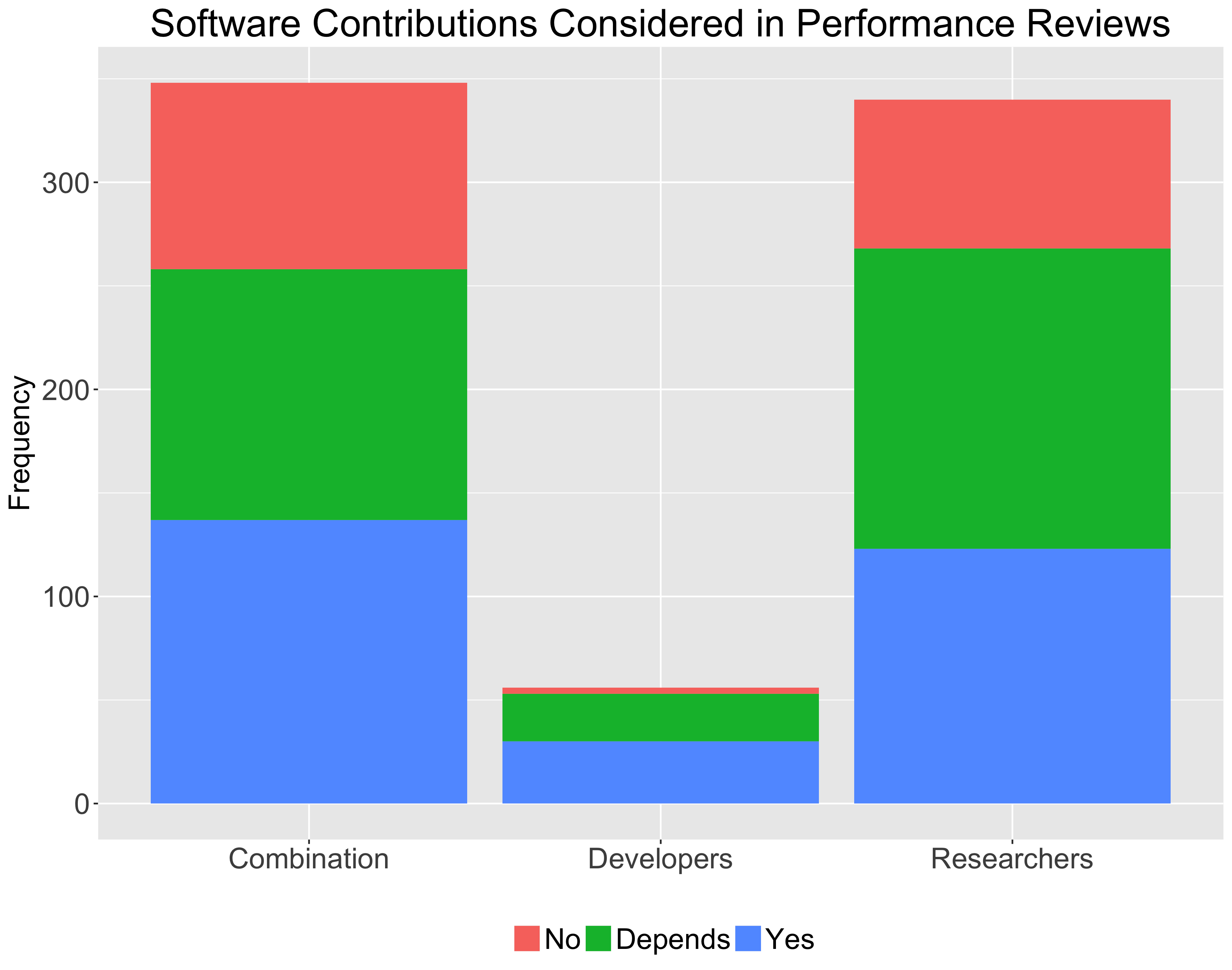

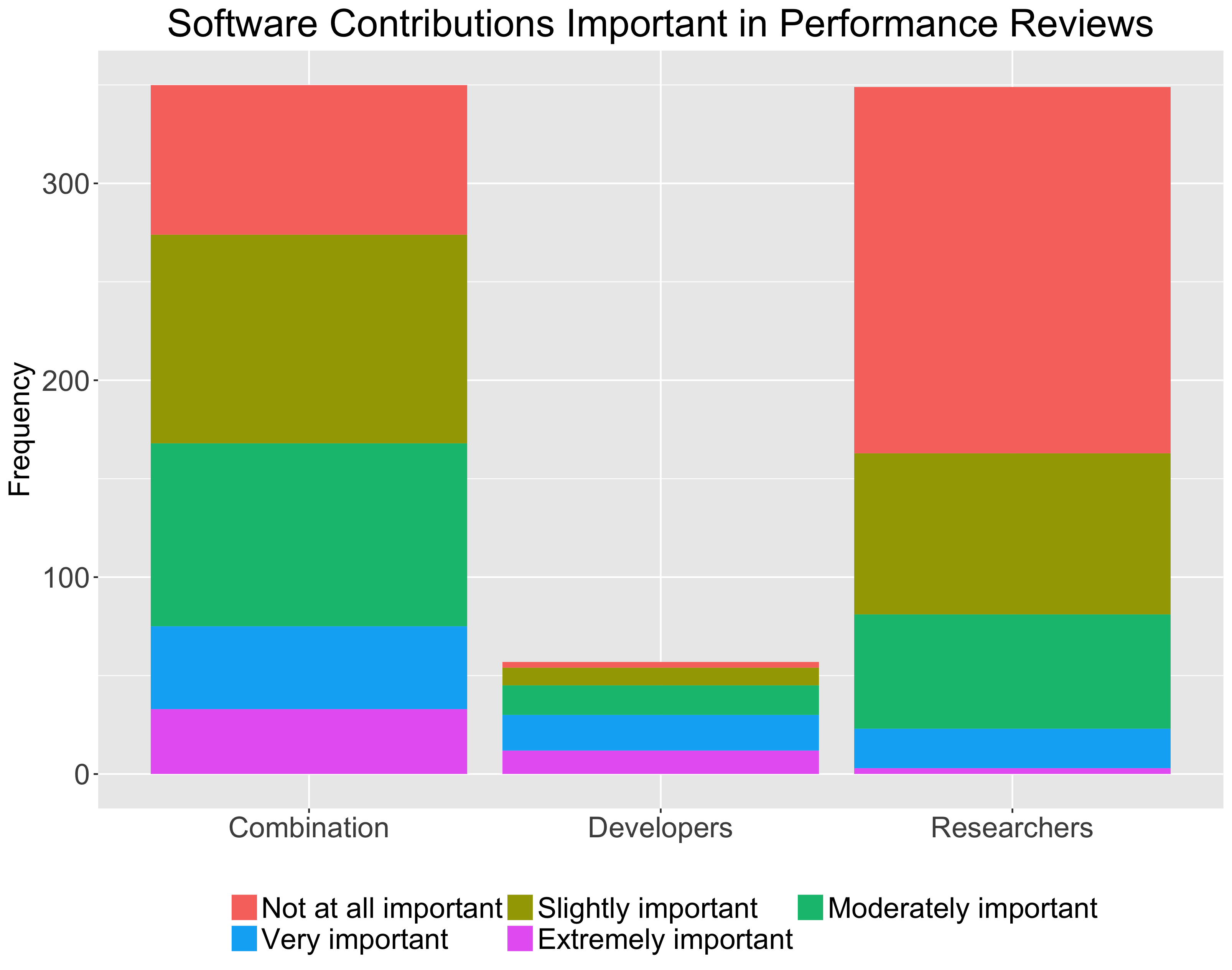

Similarly, when considering the value of software contributions during performance review or promotions, as the figures below show, while contributions are sometimes considered, they are not viewed as being very important.

Diversity

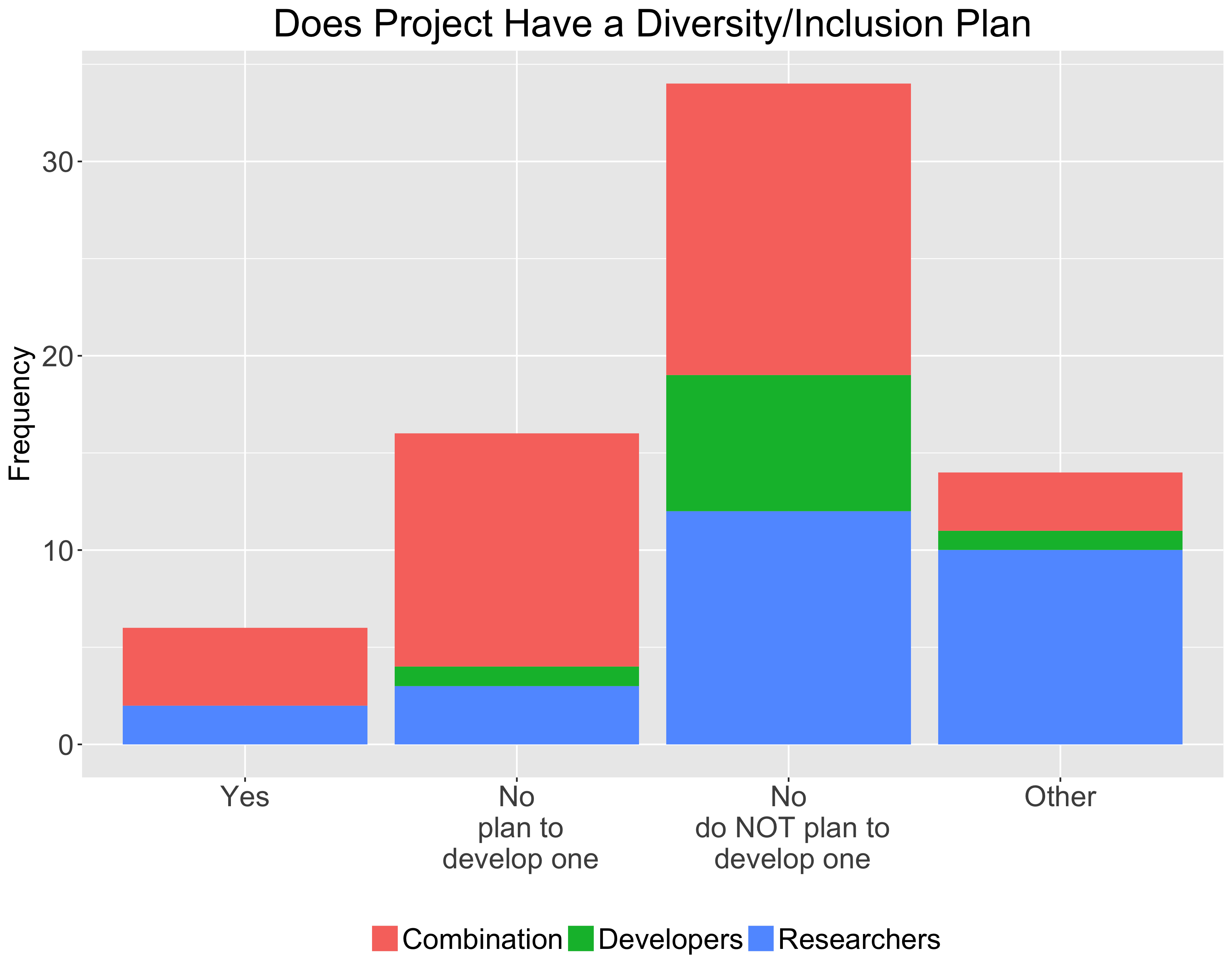

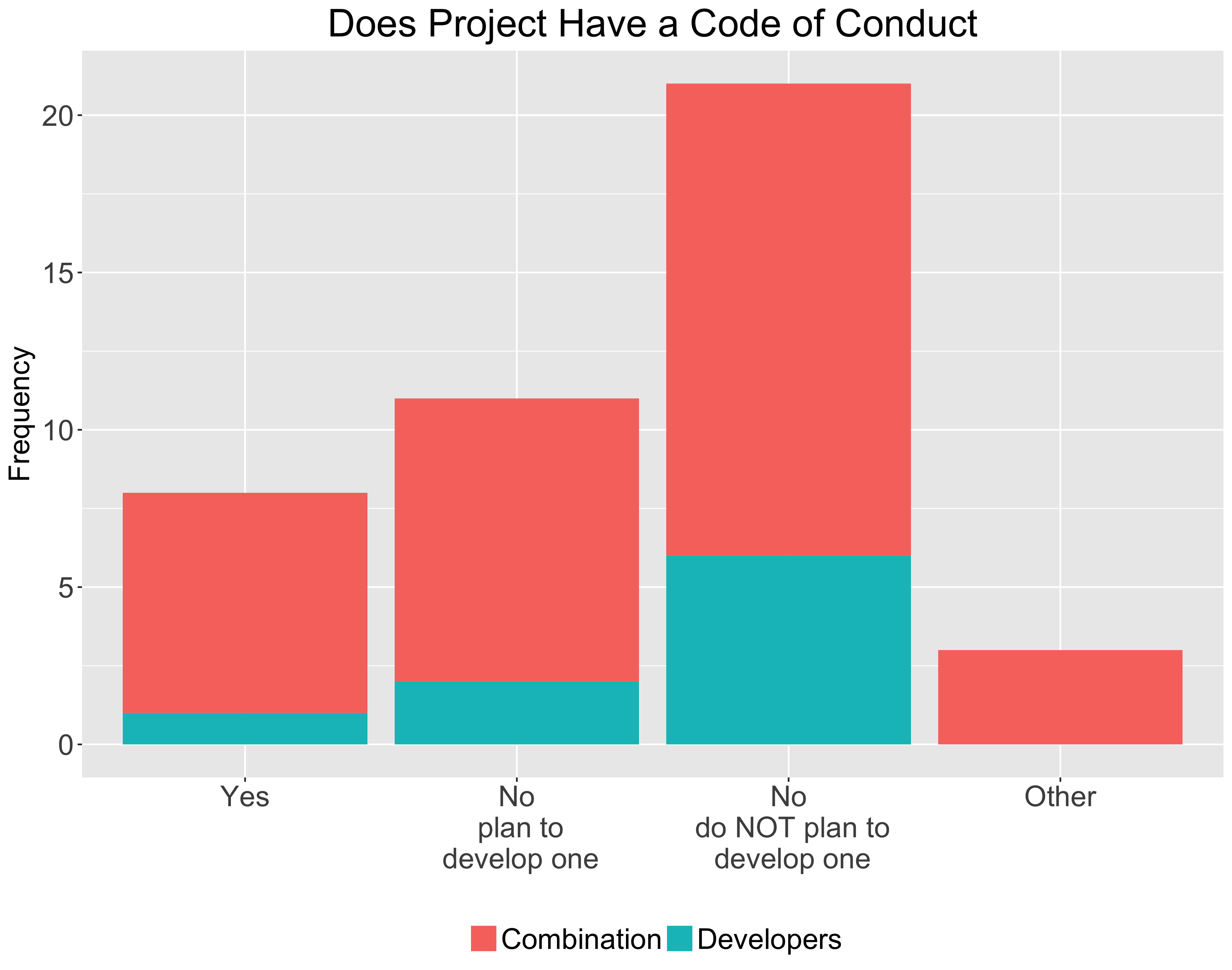

Most respondents thought their projects did an average or better job of recruiting and retaining participants from underrepresented groups. The majority of respondents thought their projects maintained a culture of inclusion. However when asked whether they have a diversity/inclusion statement or a code of conduct, see figures below , most respondents said no. And of those, most had no plans to develop one. So, while there is a perception that projects are inclusive, the tangible evidence of processes and procedures do not bear this perception out, which might reduce the likelihood of people outside a project wanting to join it.

Conclusion

Overall, we found that there is a lot of room for improvement in the software development process for research software. Respondents said many aspects of the process were more difficult than it should be. In addition, there are not enough opportunities, and more importantly time, for training about software development. The current funding models are a hindrance to the progress of research software. Institutions need to provide a more clearly defined roles and career paths that include opportunities for advancement. Finally, projects need to do more than pay lip-service to diversity, but need to take active steps in this direction.

In addition to the results presented here, we gathered open-ended responses that can help provide insight into some of these results. We are analyzing these result and working on a more thorough report.