Software Incubator Workshop: A Synthesis

February 25, 2019

Thanks for comments from: Dan Katz, Suresh Marru, Abby Cabunoc Mayes, Micaela S. Parker, Danielle Robinson, and Nic Weber.

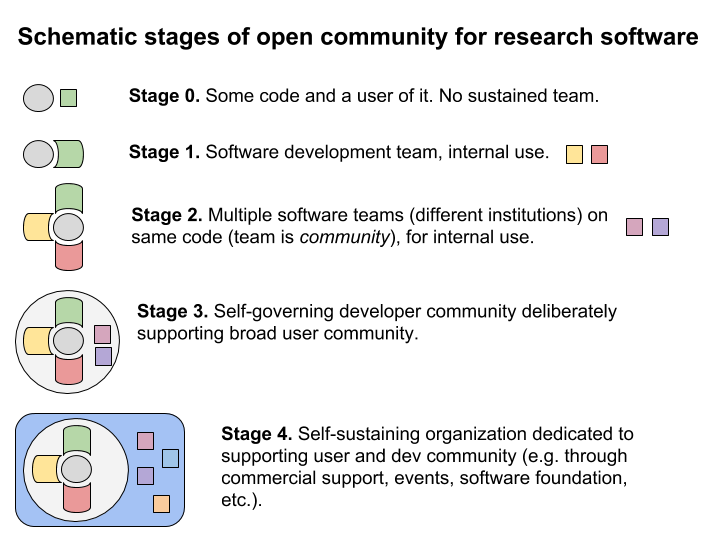

Research software is software created by scholarly researchers. Often researchers produce source code that is ‘open’, in alignment with scientific norms. But this code and the research it supports is not always “sustainable”, because it does not have a viable community of developers and users working with it in an ongoing way. For open source software in general, there are several detailed, existing taxonomies of successful open source community models, including the Apache Project Maturity Model and Mozilla’s Open Source Archetypes. Are there specific patterns of open community challenges and growth for research software that an incubator could address?

This was the question we explored at a Community Workshop for the conceptualization of a US Research Software Sustainability Institute (URSSI). Aspirationally, URSSI would be funded by the National Science Foundation. The focus of this workshop was on the possibility of an Incubator associated with URSSI, an incubator imagined as an institution that assists research software that is not yet sustainable to become sustainable. In our workshop meeting, representatives of several different open community incubators, including those dedicated to research software and open communities more generally, presented their approaches. The following model was synthesized from those cases. It characterizes several stages of a project as it grows from initial software source code to a sustainable open community.

This model is meant as a loose schematic; not all projects go through all stages. It also does not cover the entire diversity of ways open software projects can exist. Rather, this model is tailored to scientific software in particular as it emerges from one scientific lab into an open project supported by its users.

At Stage 0, there is some software code and at least one user of it. But there is no sustained team working on the code over time.

At Stage 1, a financially sustained team has formed around the software. Perhaps this is a single lab or group funded by grants. Attaining Stage 1 requires software engineering skills for the team to coordinate effectively.

At Stage 2, development on the same software is distributed to multiple institutional homes. This encourages practices of openness and collaborative software engineering. Each institution funds its contributions separately, for example from grants or university funds. Governance can be informal, but the multiple teams must discover each other and be willing to collaborate in order to achieve this stage.

At Stage 3, the developer community self-organizes with the agenda of supporting a broader user community. Documentation and governance/leadership mechanisms are necessary at this stage. This makes it easier for institutions (like businesses) to institutionally invest in their own employee’s contribution to the project. It also makes it easier to convert users into contributors.

At Stage 4, an organization serves the user community and harnesses their interest in the software to recapture value for the developer community. When the users of the software are, directly or indirectly, providing support for the community, the project is sustainable.

Current Incubators

The incubators that presented at the Community Workshop assist projects at different phases, according to this schema.

Apache Incubator. Moves from Stage 1 or 2 to 3, through shared governance model and community practice standards. Offers community governance mentorship.

Code for Science & Society. Exists at Stage 4 to support fiscally sponsored projects (Dat, Stencila, PREreview, OpenReview, M-Lab) Would like to incubate projects from 0 or 1 through to 4. Currently, can only work with projects with existing funding but produces events and resources that are openly available.

eScience Institute Winter Incubators. Incubates scientific projects from 0 to 1, and occasionally to stage 2. Offers data science technical expertise and best practices mentorship. Would like help getting from stage 1 to stage 2 for Incubator projects after the Incubator quarter has ended, when/where appropriate.

ESIP Incubator. Moves from Stage 1 to Stage 2 by uniting teams around technology. Provides incentives for collaboration and community-building activity.

Mozilla Open Leaders. Targets people with projects at any Stage including prior to Stage 0. Teaches them open leadership skills that are helpful through to Stage 3. A typical graduate is able to recruit ~2 or 3 collaborators at a hackathon. (Moves one Stage forward during the program, often Stage 0 to 1, with skills to continue moving towards Stage 3)

NumFOCUS. Exists at Stage 4 for fiscally sponsored projects. Would like incubator to bring projects from 2 to 3, to be included as 4. Provides events planning, fundraising, for communities.

This raises the question: which stages should a URSSI incubator be focused on? What stages of a project would enter an URSSI incubation process? What does “graduating” from URSSI incubation mean?

How an incubator could work

Graduating a project from one Stage to another is not trivial. Each stage requires different resources and expertise. An NSF-funded incubator could help research software along the path by first credentialing projects based on the stage that they have attained, and then offering mentorship or workshops to give teams the necessary skills to advance to the next stage.

Successful sustainability is not guaranteed for every scientific research software project. Realistically, most projects fail. This raises the important question of which projects an Incubator would invest in, and how it would decide between them, given limited resources.

One way to address this resource scarcity is for an NSF incubator to leverage its NSF affiliation as a source of incentives. NSF proposals already evaluate applications based on “broader impact” and “intellectual merit”. What if contributions to research software were considered for their broader impact and intellectual merit? What if the amount of impact and merit of these contributions depended on the stage of the software project? For example, a contribution to a project at Stage 2 (which is used by multiple institutions) could be considered to have more impact and merit than a project at Stage 1. An URSSI Incubator could support research software by advocating for changing the incentives around its development. By credentialing projects as having achieved certain Stages and suggesting changes to the criteria for grant acceptance to take these stages into account, that would orient scientific research communities towards greater cooperation on software.

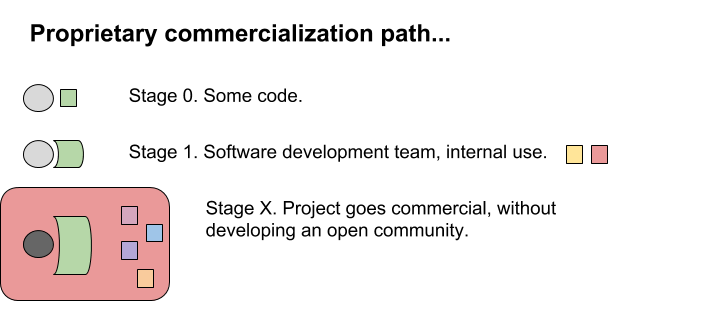

What about the commercial option?

We acknowledged, but did not discuss in depth, a different path for sustainability for research software: proprietary commercialization. The NSF supports this already through NSF I-Corps supports this.

Implicit in our discussion was the tension that science is an open process, but that science depends on technology for progress. Technology is often sustained in an industrial context. Research software, which is both technology and a way of expressing scientific ideas, challenges traditional models of “technology transfer” as a way of bringing scientific results into wider use. Our work conceptualizing an URSSI Incubator outlined one path that research software could take towards open and community-driven sustainability.